|

|

|

|

|

August 9 thru August 14, 2010 Bob Marshall Wilderness, Big Blackfoot River MT.

Time:

Narrative: “We saw the Great Bear…..so we shot at it……” Noah said as we drove the 70 or so miles from the Missoula, MT. airport to his family’s cabin in Seeley Lake. I don’t recall how we got onto the subject, but he was recounting the numerous journal entries of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. It seems they had heard of the “Great Bear”, the Brown Bear better known as the “Grizzly” from the Native American tribes they encountered and were eager to see one.

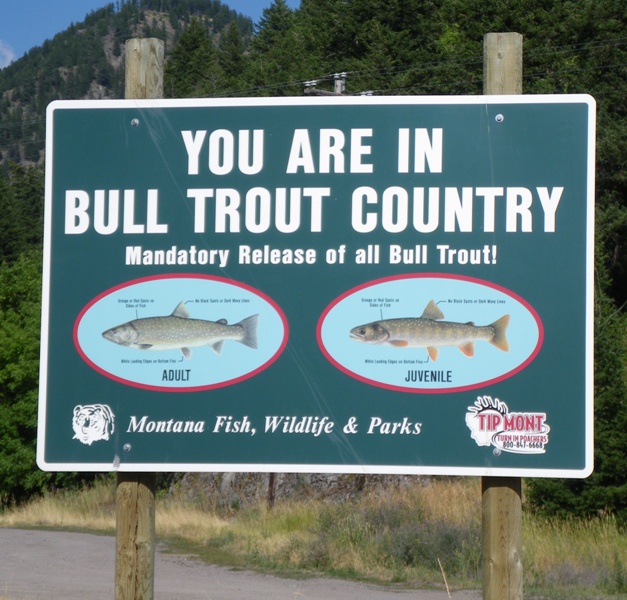

If I had any anxiety about this trip it was about the Brown Bears. It’s not everyday that you hike into a wilderness where you are not top of the food chain. Sure, in California we have lions but lions do their level best to avoid human contact and there’s not much that one can do as a backpacker to attract them…short of walking around with a gapping, bloody wound. With bears, Grizzly in particular, there’s a whole protocol of things to do to avoid unwanted contact. Some of which are very easy to forget or accidentally miss. Used to wiping your hands on your pants after handling fish? Probably not a good idea in Grizzly country if you sleep with your cloths in your tent. I was eager to see the Great Brown Bear, having never backpacked in Grizzly country before. All the reading I’d done for this trip described the Bob Marshall Wilderness as “major” Grizzly country. Our likelihood of seeing a Brown Bear was considered high. Noah had planned the trip. We arrived on Saturday and would enter the wilderness on Monday. Saturday and Sunday would be spent at his family’s 100 year old cabin, taking care of any last minute preparations and consulting the wilderness “guru” Bud- a family friend and old timer that had spent his adult life both in the forest service and trapping game in the Montana wilderness. Bud was now in his 80s but it seemed that as early as 10 years ago, he was going out into the wilderness in the dead of winter with his two Alaskan dogs to lay traps. He did a loop, he would lay them and then do it all again and pick them up. When we mentioned our plan of taking two days to hike the 26 miles to the river he said matter of factually…”I’d do it in one day, if I had nothing else to do….” Here was a real mountain man. The cabin was on the banks of Seeley Lake. It had been the first of such cabins on the lake and consisted of a kitchen, small bedroom, larger main room and an enclosed porch. Inside there were various memorabilia collected over a 100 years of occupancy- family photos, books, old fishing equipment. Noah’s family has been fly fishing the nearby Blackfoot River for longer than the cabin has existed and there was no shortage of fly gear and old flies. Forget your rod? No problem, there were more than you would need waiting at the cabin. It was at the cabin that I picked up an unabridged copy of the Journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition. The background to the expedition is a fascinating one. Not only did Thomas Jefferson have a personal curiosity about the West but the geo-political climate, the Spanish in the south, French in the North and the British looking to claim the American West as their own, made it imperative for national security. That same climate also made it necessary to hide the purpose of the expedition from those same colonial powers that controlled much of the land outside of the colonies during that period. It is real interesting reading, so much so that I picked up an abridged version of the journal at the airport for my return flight. The two days at the cabin helped us settle in and get to know each other. Noah and I had never met, though we’d been corresponding for most of the year. Bernard was our mutual link and the 3 of us had planned to spend 6 days in the Bob Marshall Wilderness in the northwest Rocky Mountains. The “Bob” is the second largest wilderness area in the contiguous United States and contains the highest population of Brown Bears in those states. We would enter at a trailhead near Seeley Lake and hike 26 miles to the Flathead River. The Flathead River is one of Montana’s last great wilderness streams. Large Westslope Cutthroat and Bull Trout were common. It was advertised by pack train operators as “fishing as it used to be”. It also contains a population of Grayling, which though not immediately known to me, focused my interest once I’d found out. We’d spend 3 nights on the river and then hike back out in 2 days. A simple, if somewhat brutal plan but we were up for it. Our first day of 12 or so miles took us up and over a ridge with 3,000 feet plus elevation gain in the first several miles. From there it would be a gradual down hill to our original elevation and the river. Each trip I learn something new, make a slight change to how I backpack or what I bring. This trip I learned that the standard procedures for sheltering from lightning need a bit of modification, for me anyway. From my reading, I’ve always followed the following procedure:

Well, in the past 3 weeks I’ve had 3 separate and different, close lightning experiences which have convinced me that I need to carry a closed cell foam pad especially for sheltering from lighting and left me wondering if I really need to ditch my pack and all metal objects. While descending from the ridge on the first day we were overcome by a thunderstorm. We knew it was coming or at least suspected. At our lunch stop beside a small lake on the other side of the ridge, we could seem the storm approaching the lake basin. It quickly past over the lake and on the other side of the ridge it quickly caught us. We kept hiking down into the valley as the storm approached. I kept score, tracking how close the storm was as we descended by counting the interval between the lighting strike and thunder clap- 5 miles, 3 miles, 2 miles, 1.5 miles….. At ¾ of a mile we scattered and sheltered.

I dropped my pack and trekking poles and grabbed my sleeping pad. I should have grabbed my rain gear, it would have only taken about 15 seconds but I knew that folks had been struck by lightning while trying to make their way to safety and no one has been hit by lightning while in the “lightning position” so I opted to forgo my rain gear until the storm past. It was a calculated risk, I could predict and delay the onslaught of hypothermia, I couldn’t do the same with a lightning strike. The trail was surrounded on both sides by high pines. I found a couple or three young pines and bushwhacked my way to a spot among but not under them. I put my pad down and sheltered just as the hail started. The temps dropped and I became cognizant of four things- I was getting cold, I still had my knife and watch on, my sleeping pad was getting drenched and all the little shrubs that were touching the trees were touching me. I wasn’t “cold” yet, just noticing the temperature drop and recognizing that hypothermia could be a concern if the storm didn’t pass quickly enough for us to resume our hiking soon. I wasn’t too concerned about the hypothermia. It kills significantly more folks in the backcountry than lightning but it’s, as mentioned earlier, predictable, preventable and I’ve always prepared for it. The first way to prevent hypothermia is to not get wet. I failed in that but I knew that I’d start hiking again and warm up, that I had very warm dry cloths in my pack and my secret weapon that most folks don’t have, is a medical condition that requires me to take medicine that when taken in too large a does, induces hot flashes. I kept close attention to my dropping core body temperature. I’ve been in the severe early stages of hypothermia before on Hot Creek and knew how to judge my condition. I’m not in real trouble until I start loosing coordination in my limbs and I would be far from that point when the storm ended. I took my knife and watch off and placed them several feet away. I don’t believe that they can attract lightning but they can cause secondary burns and if my knife was in contact with my pad, it could create a secondary channel to allow the lighting to course through my body. Likewise with the shrubs, if any of the trees were hit, I would likely get a jolt of ground current but if the shrubs were touching the tree and touching me, I could get a jolt of direct current coursing through the tree to me via the shrub. Wood’s a poor conductor but when it’s got 30,000 amps coursing through it, it really doesn’t matter. I bent back all the shrubs so that it was just me and my pad. My poor sleeping pad, it was sopping wet, unlike when Roger and I sheltered in the Emigrant, there was no way for me to keep it dry. I resolved right there and then to bring a small foam pad for such occasions and leave my sleeping pad alone. Another revelation was that my planned and typical response to rain works during light rain, as we had in the Emigrant, but against a long, heavy downpour the garbage bag I had lining the inside of my pack wasn’t good enough to keep the contents entirely dry. Parts of my sleeping bag and cloths became damp. Not enough to be a concern but enough to be annoying. Also, by being on the inside of my pack, the plastic bag might keep the contents somewhat dry but the pack itself absorbs several pounds of water. Then of course there’s my sleeping pad which always maintains a place outside of my pack and is able to shrug off light rain but not the heavy stuff. Now back from the trip, a quick glance at the National Outdoor Leadership Society’s Lightning Safety Guidelines seems to validate my general approach but suggests that one, and they state this in big bold letters, “never seek shelter near a tree”. (www.cmc.org/members/.../NOLS%20Lightning%20Safety%20Guidelines.pdf) It seems the old adage that we should head for trees for safety should be changed to “head for rolling terrain, with trees near by.” The idea being that the gentle terrain doesn’t attract lighting and suggests avoiding open areas that are 100m wide or wider. It’s all about lowering risk and frankly, some “experts” feel that the small things that we do, such as sitting on a pad or avoiding metal does little to safeguard us from the effects of lightning. Others agree that while such precautions will not safeguard us from getting struck by lightning, such precautions limit the effect of ground currents and the path such current may take over and through us. In theory, a person in the lightning position with a single contact point with the ground will be less affected than one standing with their trekking poles in hand, essentially providing 4 points of contact with the ground and a higher target. Sitting on your internal frame backpack in the lighting position seems a viable alternative to sitting on a pad so long as you avoid the metal portions of your pack, which concentrate current. Back in the “Bob”, I left my sheltering spot to grab my rain resistant soft-shell, which was tied to the exterior of my pack. We sat for 20 min. after the last thunder clap before regrouping. By this time I was starting to shiver. Once we started to hike I was surprised by how hard it was to actually warm up. I kept my wet shirt on and covered it with my rain jacket expecting to warm up fairly quickly. (I wanted to keep my dry shirt dry to sleep in.) Each time we stopped or slowed the chill came back fairly quickly. Had we gone much farther I would have removed the shirt all together. It was a shirt that “insulated” when wet but was so thin and light as to provide very little warmth. The map showed a structure of some kind exactly where we planned to camp. I hoped it was a cabin so we could avoid setting our tents up in the rain and all that that entails. Changing from wet cloths into dry cloths in a large dry space, is far more preferable than changing from wet cloths into dry cloths in a small and ultimately, as I changed, quickly dampening space. Alternatively, I would set my tent up, cover my wet sleeping pad with my emergency blanket to keep my sleeping bag dry, get into my dry sleeping bag, nosh on some protein bars (which would help stoke my metabolism and warm me up) zip closed the bag and go to sleep. Noah and Bernard were the first to the cabin and declared it locked but since I was the cold one, I decided to look for myself. The brown cabin was about 20 feet square, with a small shed attached to its rear and an outhouse on the edge of the woods. The windows were at ceiling level, boarded up and protected by barbed wire. The door was a standard door that was protected by a metal gate. Outside, two metal bars were clamped across the outside of the gate. I immediately noticed that the inside door was not locked. There was a lock for that door but the securing mechanism was folded inside and the exterior lock was unlocked. It didn’t look to me that the “locked” door was meant to keep out people, especially people with a valid need and though I didn’t consider my condition life threatening, sleeping in such a cabin could only make the situation better not worse. “Guys, if we want into this cabin, we can get in” I said as the guys started to head back to the trail. Then I unscrewed the nuts on the outside of the metal cross bars and removed them. “What about the lock?” one of them asked. The interior door was unsecured. I’d noticed that much. The exterior door actually had a locked pad lock but the pin securing the locking “flap” for lack of a better term to the gated door pulled straight out. We were in. I’m a pretty square guy, I don’t drink, don’t smoke, consider myself a person of high integrity and would never consider breaking and entering and I don’t consider this breaking and entering, though some might. I really don’t think the cabin was “locked” to keep people out. If that were the case, the interior door would have been locked. The unwritten wilderness ethic states that folks with a valid need can take such liberties and I considered our current situation- me in the early stages of hypothermia, late in the day with dropping temperatures and continuous rain, valid circumstances. We weren’t in a survival situation and I was confident that we would NOT be but one bad night and we very well could be. We entered the cabin without damaging anything and left it exactly as we found it, adding a thank you note in the cabin log. Welcome to the Bob Marshall Wilderness Hilton. The cabin was very well stocked. Next to the door, was a wood burning stove for warmth, to the left of the door, against the left wall of the cabin were supplies and a gas burning stove for cooking, along the right wall a table and along the back a bunk bed with bed rolls and pillows. We planned on sleeping on the floor and touching nothing but as darkness approached (it became dark after 9pm here) and we got more comfortable with our surroundings, we decided to take some liberties….. Noah was the first to break out the bed roll and spread his sleeping bag out across the lower bunk. I followed suite with the upper bunk and before Bernard knew it, we were both sprawled out. He took the floor. Shortly there after Bernard discovered a stash of magazines, which included several outdoor and fly fishing magazines. After several hours I was toasty warm and reading American Angler by headlamp light. The next morning we awoke early, put everything in order, swept the cabin and headed down the trail. We had 14 plus miles to cover from the cabin to the river. Plus, because a few miles from the cabin we ran into a sign saying “14 South Fork Riv”. Indicating that we had 14 miles to travel from that point….. It was going to be a long day.

Long as it was, 14 slightly downhill and flat miles are not the same as 14 up hill miles and we were grateful for that. We’d tackle the uphill portion when our packs were lighter. It was a tough trail to develop a rhythm on. It was greatly overgrown for most of its length, which made the placement of trekking poles difficult. We arrived at the river in early evening just as Noah had predicted and had time to set up camp and fish a bit. We camped on a small beach next to the river with a small grove of dead trees and low shrubs. The trees were fire damaged, no doubt due to a lightning caused fire. The main trail lay above us on a small plateau. That first night I did a small walkabout. One striking feature was the horse corral just down the trail and on a slightly higher plateau. It was a huge permanent structure and as we fished over the next few days we’d see more. It’s seems the horse packers shuttle people in and out of this area all summer. One fellow spent his summers there, manning their camp while his fellows shuttled folks back and forth from the trailhead. His camp looked quite comfortable with a permanent latrine, hammocks and mess tents and I’m sure they had plenty of beer on hand. One disappointing by product of the horse packers in general was the amount of human waste that was evident. I guess I’m old school; I bury my waste and burn the toilet paper. I know the forest service no longer advocates the burning of toilet paper for fear of forest fires but these people in some cases didn’t even bury their waste. In other cases there were shallow cat holes with paper sticking out. The only saving grace seemed to be that there were in designated areas that once identified, could be avoided. The next day we fished in earnest. We hiked upstream hoping to get away from the crowds but there always seemed to be someone above us. That said, the river didn’t feel crowded. I had brought two graphite rods instead of my normal cane fishing tools. I brought a 6/7wt St. Croix Imperial and a 5wt Sage LL. The Sage LL is one of the best graphite rods ever made and the St. Croix, is well, a piece of crap and I’d forgot how much I hated to fish with it. I’d brought the heavier rods due to the heavier duty fish that we MIGHT get into. There was a very real possibility of catching a record fish on this trip. For me that would have been 21 inches or greater. The Cutts grow big but the Bull Trout grow bigger. It’s not unusual to be playing a 15 inch Cutthroat and have a 30 inch Bull Trout try to take it away from you. By the end of the first day I was missing my 4wt cane and wishing that I’d brought it. I missed my friend; I always have trouble adjusting when I switch rods. I know, it’s the “Indian” not the “arrow” but that doesn’t change the fact that with my cane rod casts are confident and predictable. It took me a little while to adapt, to the rod, to the fishing. I don’t do much big river fishing. I’m more used to sight fishing with short drifts to specific lies. I could have sight fished here and probably should have; I might have had a better hook up ratio but I chose instead to cast to likely holding water. It took me a while to get used to not picking the line up once it past where I thought the fish was and to let the fly drift through the remainder of the run or continuing to mend line after the fly past a likely holding area and I never did figure out why I missed so many fish- probably too much slack line. Despite all that, I caught a bunch of fish and missed a ridiculous number of fish whose type and size I can only imagine by the fish caught by Bernard and Noah. It was mid-afternoon on our first full day when I first heard the shout. I was hop scotching over Bernard and Noah who had made their way pretty far upstream when I heard Noah yelling. I couldn’t quite make it out but I thought I’d heard the word “Bull”. Coming from opposite directions, Bernard and I ironically met at about the same location and made our way together downstream. Noah’s rod was doubled over and as we got closer we could see a large shadow holding motionless in the water. Noah recounted the story; he’d approached the run and made a number of casts without seeing any action. This was unusual because you could pretty much count on multiple strikes at each run. Then, like the surfacing of a large submarine, something made a head to tail rise, bringing its body entirely above the surface of the water. He set the hook and couldn’t believe his eyes. Bernard, who is a big fish fisher and guide in the fall for big brown trout, gave instruction while I took Noah’s camera and filmed the entire fight in movie mode. Noah simply held on for dear life while the fish made run after run. It was tiring work but after 20 minutes he finally landed a 25 inches plus Bull Trout on a dry fly! We didn’t get a proper measurement but looking at the photo and knowing that my elbow to fist measurement is 15 inches and knowing that Noah is taller than me, I think from the picture it would be easy to guess that the fish is probably close to 36 inches long. It was a great fly fishing moment and the fish of a lifetime. I’m glad I was there to share it with him. It wasn’t too long after that the evening storm clouds seemed to be approaching so we headed downstream to fish closer to camp. I can’t recall if it was that night or the next day but Bernard too would catch a Bull Trout, two in fact. Not really a surprise from someone that throws more streamers during a year than dry flies and nymphs combined. The big fish hunter was in the house doing what he did best, catching 20 inch Cutts and Bulls. My own fish topped out at about 18 inches. Sunday I remembered that the stream held Grayling and decided to target them instead. Not an easy task given the fact that I knew almost nothing about the habits of Grayling and how to fish for them. I knew they had small overhanging jaws, which meant that small flies were the preferred method for fishing for them. I also knew they had a preference for peacock. In fact, now that I’m writing this, I recall that Frank Sawyer’s Killer Bug was created for Grayling. Not that it matters, I didn’t have my lake fly palate with me and hence no Killer Bugs. I think I’m pretty honest with myself about my fishing skill- prospecting with long leaders and long drifts- don’t do well. Fishing with short drifts to sighted fish or pocket water- do, do well. Upstream from our campsite there was an area of pocket water. I was in my element. I tied a small beadhead, peacock bodied softhackle to a hopper and the fish came thick and fast. In retrospect, I should have considered the number of 16 and 17 inch Cutts a sign that I was fishing the wrong water for Grayling but I was having too much fun and these fish were a tad darker and more colorful than I had fished to a day previous. They looked like what I expected Westslope Cutts to look like, yellow with black spots, orange bellies and a prominent slash mark. My trip was made right there and then. More than anything- more than numbers, more than size, I enjoy catching beautiful fish. That night we hiked up the trail 5 miles to camp at the inlet of a large lake that was on the trail back to the trailhead. This would hopefully allow us to make it up and over the pass where we were caught in the thunderstorm and make our last day an easy 6 or so miles back to the car. It would be roughly 14 miles and gradually up all the way. It was a pretty grueling day despite our lighter packs, characterized by lots of miles, lots of wild huckleberries and several longish meal stops. Our hike back was perfectly timed with the ripening of several huckleberry patches and as I lead the group up the trail I’d often call out a huckleberry alert. To which we’d stop and grab a handful of huckleberries before continuing on. That last night was spent on Upper Holland Lake. I spent 40 or so minutes fishing the lake, which gave up Cutts in the 7 to 12 inch range. They looked slightly different than the stream Cutts but may have simply been the lake strain of the same fish. The next morning on the hike down to the cars we stopped along several sections of the trail that followed the outlet stream from the lake. Bernard and I climbed down a steep hill with fallen timber to the base of a high cascade. Bernard wanted to fish the log jam at its tail; I wanted to fish the walls of the rock on either side of the plunge. Bernard picked up a few fish subsurface immediately. I then followed behind him with a dry fly. I don’t recall if I started catching fish on a dry immediately. I think I may have drawn a strike on a cripple caddis but wasn’t seeing the action I thought I should so I switched to several different dry flies. It wasn’t until I put on an ant that I started to see regular action.

The black ant is one of my staples but it also doesn’t float well at times and it was one of those times when the fish slammed the fly without hesitation. The water was clear and in most cases I could see the fly as it drifted subsurface. For a while it was catching fish pretty regularly. At some point I decided to put on my black softhackle bead head pattern. I really should come up with a name for it, some times I call it a black bead head or black softhackle or beadhead black softhackle, when I do, I’m always referring to the same pattern, though it might not seem like it. It seems almost pretentious to name it but it would make it easier on the reader I’m sure. Anyway, Bernard had coaxed a largish fish out of the logs on my side of the pool but missed it. As I sometimes do, I started experimenting with different flies, just to see how the fish would react to them- make a cast, put on a new fly, make a few more casts, do it all over again. I was heading back up to the trail when I decided to dap either the black softhackle or its gold ribbed hares ear cousin, into the long jam. A couple of twitches is all it took to induce a charge from the big boy. I’m not sure if it was the same fish as Bernard’s but it was the largest fish we’d seen. It was darker than the others, as fish in woody debris tend to be, with an almost golden hue to it. I wish I could have photographed it but I’d left my camera in my pack on the trail. Bernard had the only camera and he’d already climbed back up the hill so the image will simply have to live in my memory. We stopped again on the trail and Bernard showed again why he is a big fish catching machine. In an area I was sure the fish had been put down in, he picked up a fish that dwarfed any that Noah and I had caught by 2 or 3 body lengths. Then he crawled up the bank, handed me back my rod and said….”That was fun….”

The end of our trek was followed promptly by a shower, hamburger and Huckleberry shake, though not necessarily in that order. That evening we hit a fairly crowded Blackfoot River. Each parking area seemed to be full as we drove the access road that follows the stream just outside of Seally Lake. “Gee, there seem to be quite a lot of people fishing this steam” I thought to myself. “Lots of folks floating the river”, Noah kept saying. After some cross discussion it was revealed that folks were floating the river on inner tubes and kayaks, not float fishing the river. We lucked into a spot at one of the far downstream access points. A fish and game guy and his partner were packing up their gear. I don’t think we ever did ask what they had been doing but we struck up a conversation, telling him about our recent trip to the Flathead and lamenting the amount of horse travel on the trail. “That’s a good walk” he said of the former, he seemed rather unsympathetic about the latter. The horses had become a particular nuisance by week’s end. Not simply because there were so many of them, and there were….. there should be some sort of quota. Not simply because the riders seemed to be rather unruly and without wilderness manners. Not simply because they didn’t seem to understand the concept of “leave no trace” but for the simple reason that there seemed to be inexperienced riders on inexperienced horses and that put our lives in danger. No fewer than twice had horses become unnecessarily rambunctious around me and I know it happened to the others as well. In one case, the rider took control immediately. In another, the rider let the horse turn about a little too long and was obviously not in control, causing me to step further toward the side of a steep drop than I was comfortable with. Noah was incensed and ranted for the next half hour about writing to the forest service and complaining. I hope he does too. I don’t think the whole “its part of our heritage” bit holds water when there are so many pack trains going into the wilderness simply for profit and at the same time not being good stewards of the wilderness. The Big Blackfoot reminded me a lot of the Stanislaus in the Central Valley. Wide with deep, boulder filled glides; it’s a stream that screams “fish Hickson/Schubert right angle method here.” Bernard, being a previous fishing partner of Hickson, did just that! Noah and Bernard headed upstream immediately while I waded out into the deeper water. The water was warm and I did my best to fish the runs and boulders in the Humphrey’s style. A thin running line would have been handy here, to prevent the current from catching my line in the runs closer to the opposite bank. Where the wakes of two boulders met and formed a “V” I managed to hook my first fish. It was a good fish but I promptly put a bit too much pressure on and lost it- fun but no fish. I fished out the run and then headed upstream to meet with Bernard and Noah. Bernard had already released a nice brown. (I’m not quite sure how it is Mr. “I spend my Fall fishing for Brown Trout” managed to catch the only Brown Trout among the 3 of us that night. But I guess, given the aforementioned title, I shouldn’t be surprised.) Noah began to make an art of catching Blackfoot trout on dry flies while Bernard and I fished subsurface. I’d gotten a few more takes but no solid hook ups until Noah moved upstream and I moved into position where he was fish. I was sure my flies were traveling too fast and not deep enough so I put on two heavily weighted nymphs. I rarely fish such a heavy rig but seemed to have little trouble controlling it. I imagined the two nymphs twisting and encircling each other like two halves of a throwing bolo but that didn’t happen. On the third cast with the new set up I hooked into a solid fish and when I landed it, my size twelve nymph was sticking out of its nose like a piercing on a Cal Berkeley Co-ed. (Co-ed, did I just date myself? Probably not PC, maybe even a little sexist but I'm sure it conjured up the right image....) Shortly there after we picked up and moved further up river. The fishing here was tough. I managed to catch 2 smallish rainbows. It’s ironic that a trip that had thus far been predicated on 16 to 25 plus inch trout should end with 2 trout of about 8 inches. Our week had been a wild ride of big sky, big trout and big storms. I’m sure I’ll get back to Montana (after all, I was the only one that didn’t catch a Bull Trout and the Grayling are still calling) but I may never experience its like not again. I’m fortunate to have shared the trip with two fellows such as Bernard and Noah and to have had experienced fishing the “way it used be”. Perhaps next time, we’ll spot “The Great Bear”

Next Other National Forest Chronicle Chronicle Index

|